ATD Blog

Gender Bias in the Classroom: Oh No, Not Mine! A Quick 7-Point Self-Assessment

Mon Mar 13 2017

For decades, we have acknowledged that when young girls’ self esteem is eroded early in their lives, it can have a negative lifelong ripple effect on their educational choices, career options, and pay.

Peggy Orenstein and the American Association of University Women highlighted the alignment of low esteem, low competence levels, and low life and career expectations in School Girls: Young Women, Self-Esteem, and the Confidence Gap. The book examined the role of classroom gender bias in eroding confidence of girls. Boys were encouraged to engage in more assertive classroom behaviors such as speaking out and presenting dissenting views to teachers. Boys tended to receive more attention from teachers.

While School Girls was published in 1995, more recent studies have confirmed this gender bias still exists in our classrooms, leading to a gender gap that continues to plague the United States. For instance, the World Economic Forum reports that the United States slipped to 45th in the 2016 world gender gap rankings.

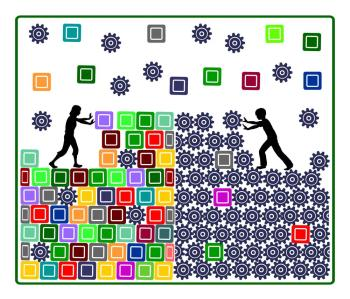

The cumulative impact of small educational experiences can be life-altering. With record numbers of women now attending college, as educators, we have an opportunity (and an obligation) to address this issue. If we are not consciously creating an environment of equality, we may be perpetuating the problem of gender bias.

Does your classroom exhibit signs of gender bias? While most of us would automatically say no, I would encourage you to first review this checklist and then thoughtfully consider how you might guard against gender bias creeping into your classroom. And ladies, don’t stop reading. Female professors can also exhibit gender bias!

In conducting a self-check, we might consider the following points:

Do we respond (in emails and in class) equally to both male and female students? Studies have shown a tendency for educators to respond more to male students.

Do we engage in subtle favoritism? Male students are often given a pass on behaviors deemed inappropriate for female students (such as talking out of turn or over others). Studies have found males interrupt females more often than other males.

Do we perceive higher rates of participation by male students? Research has found professors perceive male students’ participation rates to be higher than female students’ participation rates. Females can be at a disadvantage, then, when a portion of the grade includes participation.

Do we expect more cooperative behaviors from female students? Studies have revealed a gender bias toward expectations for females to engage in more cooperative behaviors (or getting along), while expectations focus more on competitive behaviors for males.

Do we provide opportunities for success (especially in teams) equally to male and female students? Women sometimes opt out of leadership roles and the challenging assignments. Part of building confidence is to stretch—and succeed.

Do we let males take credit and women take the blame? Females are more likely to apologize and accept the responsibility for failed assignments. Males are more likely to take credit for successes. Lessons in accountability for all students are important.

Do we accept our role in addressing gender bias? As educators, we have a responsibility to help address gender bias in the classroom by modeling appropriate behaviors and helping shape appropriate behaviors in our students. The website created by Andrea Kramer and Al Harris provides a free assessment to test our ability to navigate gender bias.

Sexism persists in the workplace: Rosalind Barnett has described gender discrimination as being “underground” but not resolved. In helping our students develop the life skills required in the real world, we must accept the call to action for gender parity.