ATD Blog

Build Context Into Conversations to Improve Workplace Well-Being

Thu Jul 25 2013

Virtual distance slows the development of social well-being. The first blog post in this series described one way this happens: Relying heavily on electronic communications creates virtual distance and thwarts sensory and cognitive perceptions. Without these invisible antennae, it’s nearly impossible to interpret proper meaning from any given message. One difficulty stems from a lack of context.

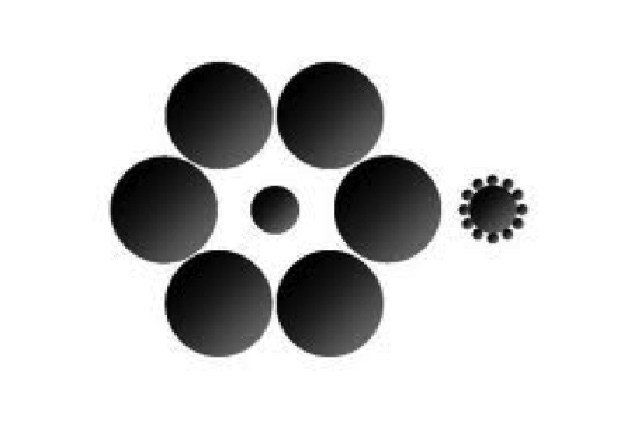

Consider the following picture:

After a quick glance, the circle in the middle of the left image seems smaller than the center circle on the right. This is because the circles around the left center image (the context in which it’s presented) are bigger than the ones on the right, so the inner circle appears smaller. But in reality, both circles are the same size. The context, or framing, of the center circles creates an illusion.

Virtual team players often suffer from the same kind of illusions. Individuals often ascribe certain meaning to electronic interactions based on false frames. Analogous to the diagram, when people talk to each other, either face-to-face or over the phone, they can “see or hear the circles around the center,” so to speak. This establishes a shared context. But in virtual spaces, mutual context disappears. Team members don’t have access to contextual markers as a way to decode conversations.

Often mistaken meaning and misunderstandings ensues. As social well-being cracks, virtual distance increases, civil discourse declines, and performance suffers as a result. To counteract this phenomenon, managers and team members must be trained to intentionally inject context into as many interactions as possible. Here are two simple steps to restoring shared context.

1. Be aware that context is missing. This first step may seem too simple. But unbeknownst to the average employee, a lack of context is not the first thing that comes to mind when, for example, someone receives an email that hits him the wrong way. Employees must be trained to provide contextual information as often as possible. They also should learn how to detect missing context—to be taught when and how to obtain more information—before coming to any particular conclusion.

For example, during typical virtual meetings, something as simple as explicitly stating the location, time, and temperature of each team member’s location helps to establish a shared perspective and reduce virtual distance.

2. Train managers and team members on best practices specifically designed to restore shared context. Knowing how a team member’s role fits within the larger picture is a crucial contextual factor. One’s location and objectives in relation to others often are unknown among the virtual workforce, so managers must learn best practices for continuously illuminating everyone’s roles and goals. For example, with traditional meetings held in conference rooms, employees can quickly identify each person’s relation to others simply by observing where and with whom people sit.

In the virtual space, there is no table. In the absence of these kinds of contextual cues, people make assumptions about a perceived leader or other team players. These assumptions almost always are wrong, or, at best, incomplete. So managers need to learn how to compensate.

One way is to detail team members’ roles and goals by regularly and publicly describing their responsibilities in light of the larger picture—including ties to the customer. In particular, during the first virtual project team meeting, the leader should go around the virtual table and ask each person to share what she understands to be her role and goals. The leader then should echo the team member’s response and, in addition, shed light on anything the team member left out—thereby strengthening the leadership stance.

In sum, the context embedded within a traditional environment, whether it be gestures, shared physical space, points of view, or some combination, hides in dark corners of virtual spaces. Managers must find and illuminate what matters most. This will help to decrease virtual distance, rebuild social well-being, and improve performance.

Although coloring in the whole picture by restoring shared context is critical, there are times when being face-to-face is vital to success. The next blog post will debunk widely held beliefs about face-to-face versus virtual interactions and suggest ways to train employees how to determine when this is critical and when it’s not.