ATD Blog

Connecting Mindfulness, Computer-Based Brain Training, and Self-Awareness

Thu Oct 09 2014

At the CIMBA Leadership Labs, we have observed that almost any development intervention benefits from both mindfulness practice and computer-based brain training to enhance self-regulation. In concert, mindfulness and enhanced self-regulation ability also serve to influence an individual’s self-awareness.

Interestingly, with regard to the latter, virtually all literature discussing the brain and behavior prescriptively asserts self-awareness (in one form or another) as a "solution" to the particular malady it addresses—something with which we are in general agreement.

Recent research on mindfulness

Our understanding of the importance of mindfulness practice continues to grow, with recent research demonstrating its positive affect on decision making (Hafenbrack et al., 2013), creativity (Colzato et al., 2012), emotion regulation (Teper et al., 2013), and self-regulation (Tang et al., 2014). Collectively, these findings raise the possibility that mindfulness interventions produce specific plasticity-related alterations in brain function and structure.

Successfully navigating a social transition means efficiently and effectively reading and comprehending social cues (see Olsson et al., 2013). To this end, supported interventions that enhance empathetic accuracy and related neural activity are likely to prove beneficial to individuals in leadership positions.

Consequently, it is not surprising that mindfulness practices that emphasize the cultivation of positive affect, such as compassion and kindness, have received increased empirical attention. In fact, Hofmann et al. (2011) concluded that mindfulness interventions oriented toward enhancing the positive emotions of compassion and kindness do increase positive affect and decrease negative affect.

Two additional 2013 studies provide further support for this notion, one promoting the benefits of a secularized analytical compassion meditation program, cognitive-based compassion training (Mascaro et al., 2013) and the other a compassion mindfulness practice led by an experienced instructor (Klimecki et al., 2013).

In addition to better understanding their emotions and emotions of others through mindfulness practice, leaders need the self-discipline to generate results. Tang et al. (2014) found that mindfulness meditation is effective in improving brain function related to executive attention. Although the study focused on the use of the mindful meditation technique, Integrated Body-Mind Training (IBMT), a powerful technique introduced to CIMBA by Tang several years ago, several other forms of mindfulness also have been shown to enhance self-regulation (Davidson & McEwen, 2012).

Mindfulness practice supported by technology

The body of research supportive of mindfulness continues to grow impressively. Several major companies now offer the opportunity for employees to participate in a variety of programs. At CIMBA, we have found that the use of physiological measurement instruments, such as a Fitbit or heart rate monitor, can have an impact on mindfulness by raising an individual's awareness of his or her body's physical and mental responses to stimuli, something referred to as "interoception."

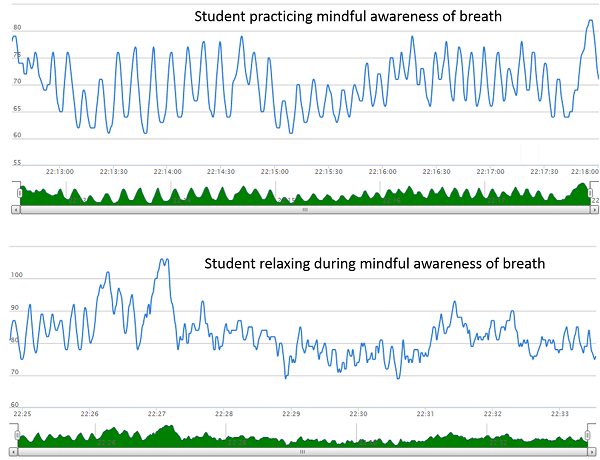

In addition, physiological measurement instruments can be used to assist novices through the "It doesn't work for me" phase. As illustrated in the figure below, physiological data collected during an individual's practice can be compared to data where the practice—in this case, an awareness of breath exercise intended to assist with mindfulness—was performed correctly.

This data also can be used to assure an individual's coach—personal development coaching being an integral aspect of the CIMBA Leadership Labs’ leadership system—that the coachees’ time is being spent productively. Without this type of technological assistance, coaches would have to rely on either self-report data or observed behavior change to have any idea of the effectiveness of the mindfulness intervention.

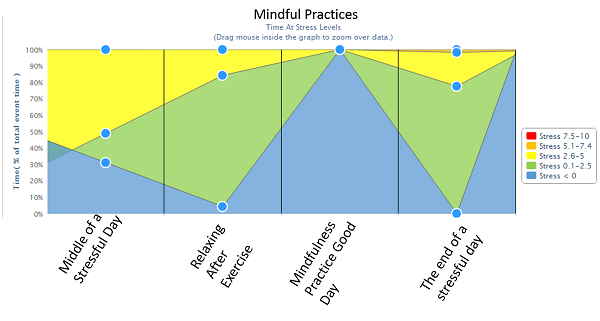

At the CIMBA Leadership Labs, we have additionally developed software to allow an individual to compare mindfulness sessions and his or her physiological reactions to other stressful or emotional events, working with a coach all the while in an effort to improve his or her response to such events. The heart rate monitor delivers a physiological assessment of stress using heart rate variability.

As illustrated in the figure below, the data from a variety of sessions—for example, after a stressful day, during a stressful encounter, and after a period of exercise or relaxation—provide insights into both the effectiveness of a mindfulness "moment" and the events in our day-to-day lives that create stress.

References

Hafenbrack, A. C., Kinias, Z., & Barsade, S. G. (2013). Debiasing the Mind Through Meditation Mindfulness and the Sunk-Cost Bias. Psychological Science, 25 (2), 369-376

Colzato, L. S., Ozturk, A., & Hommel, B. (2012). Meditate to create: The impact of focused-attention and open-monitoring training on convergent and divergent thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 3.

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: How mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 449-454.

Tang, Y. Y., Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (2014). Meditation improves self‐regulation over the life span. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1307(1), 104-111.

Olsson, A., Carmona, S., Downey, G., Bolger, N., & Ochsner, K. N. (2013). Learning biases underlying individual differences in sensitivity to social rejection. Emotion, 13(4), 616-621.

Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126-1132.

Mascaro, J. S., Rilling, J. K., Negi, L. T., & Raison, C. L. (2013). Compassion meditation enhances empathic accuracy and related neural activity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 48-55.

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Lamm, C., & Singer, T. (2013). Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex, 23(7), 1552-1561.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature neuroscience, 15(5), 689-695.

www.huffingtonpost.com/karen-s-exkorn/mindfulness-practice\\\_b\\\_4763160.html