ATD Blog

Do Online Agents Improve Learning?

Tue Feb 19 2013

Attend the Evidence-Based Learning Virtual Conference, and learn more best practices like these from 6 of learning’s top thought leaders.

In a recent blog post, I discussed the benefits of social presence during learning. Higher social presence leads to higher course ratings, and if properly implemented, also improves learning. I think that asynchronous self-study e-learning demands special attention because by definition, these courses are designed to be taken by individuals working mostly in a solo mode. In this post, I’ll discuss the use of online agents to increase social presence and improve learning.

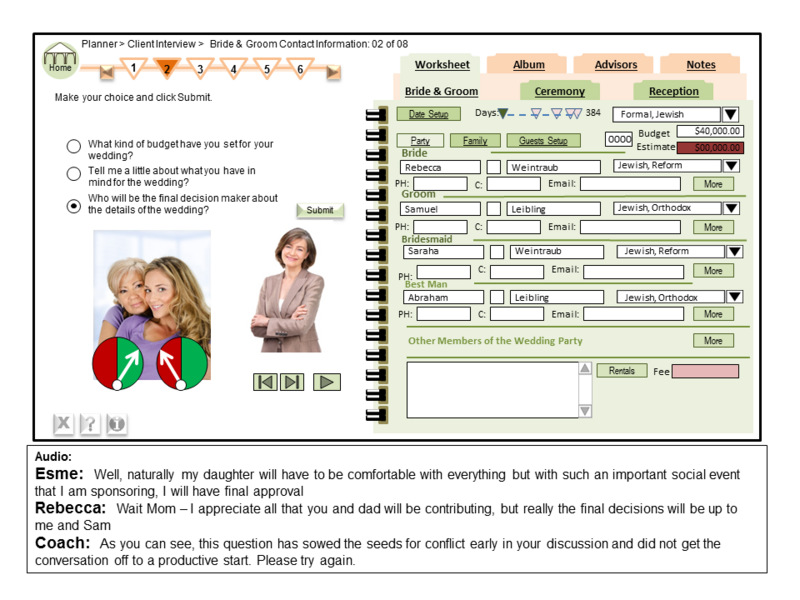

Take a look at the screen shot below from a course I designed for new wedding counselors. As you review the images and audio, consider the following questions:

A. Which image represents the online agent?

B. What role is the agent playing in this segment of the course?

An on-screen Agent Used in a Wedding Counselor Course. From Clark, 2013.

What Are Online Agents?

Also called pedagogical agents, online agents are onscreen personas that serve a relevant instructional purpose. Agents may take the form of a realistic human image or a cartoon image of a character such as an animal or an inanimate object. In the example above, the image of the woman on the right is an online agent serving as a coach. In this part of the course, the learner has selected a question to ask the clients, and feedback consists of clients’ audio responses and clients’ attitude meter, supplemented by audio comments from the agent.

Evidence on Online Agents

A comprehensive review of the effects of online agents concludes that evidence does not support general recommendations of agents for either learning or motivational purposes (Heidig & Clarebout, 2011). Instead, we will need to build guidelines that take into account (1) features of the agents (2) instructional role of the agents, and (3) features of the learners. Toward that end, a series of recent experiments have compared learning from an agent that exhibited human behaviors versus the same agent that merely appeared as an onscreen static image (Mayer & DaPra, 2012). These experiments have started to define agent features that promote learning. Lessons learned so far are:

Agents should serve some relevant instructional role. Simply putting an image on the screen does not necessarily promote learning. Instead, the agent should serve and instructional function by presenting information, giving feedback, and/or providing examples. More research is needed to identify what specific instructional roles are best assumed by agents.

Agents should exhibit human-like behaviors. In a 4-minute presentation on how solar cells convert sunlight into electricity, the agent presented an audio narration of the content. A high-embodiment agent used natural gesturing including pointing, conversational gesturing, posture changes, realistic facial expressions, and eye gaze shifts to direct attention. The low embodiment agent held a casual posture, kept eye gaze straight ahead, showed no change in facial expression, and did not move. A third control group listened to the same content in the absence of an on-screen agent. Transfer of learning was best from the high-embodiment agent (Mayer & DaPra, 2012). Similar results were reported by Lusk and Atkinson (2007).

Agents should sound real. In a second experiment in the Mayer & DaPra research, learning benefits of a high- and low-embodiment agent using either a human voice or a machine voice to present the information were compared. The group with the high-embodiment agent that spoke with a human voice learned significantly more than any of the other groups.

Online agents that exhibit human-like movement are likely to be perceived by learners as social conversational partners. Online Agents: A Work in Progress

Online agents that exhibit human-like movement, use eye gazes and speak with a human voice are likely to be perceived by learners as social conversational partners leading to deeper processing of the content. Agents are one technique to increase social presence in asynchronous online environments.

However, we still have a lot to learn about the situations in which agents are and are not beneficial. For example, we need additional research to determine the extent to which learning will be affected by: (1) different agent features such as sex or ethnicity, (2) different content such as social skills versus technical skills, (3) different functionality such as to present content or to give feedback, and (4) different learner populations. For now, I recommend testing a prototype agent with a sample of your learner population. Design an agent with realistic, human-like features described above, and give the agent a relevant instructional purpose.

Your Lessons Learned

Have you tried onscreen agents? Who was your audience? How did they react to the agents? Was learning improved? For what purpose did you use the agents? Please comment with your own lessons learned.

References

Clark, R.C. (2013). Scenario-based e-Learning. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Clark, R.C. & Mayer, R.E. (2011). E-Learning and the Science of Instruction. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. See Chapter 9.

Heidig, S., & Clarebout, G. (2011). Do pedagogical agents make a difference to student motivation and learning? Educational Research Review, 6, 27-54.

Lusk, M.M., & Atkinson, R.K. (2007). Animated pedagogical agents: Does the degree of embodiment impact learning from static or animated worked examples? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 747-764.

Mayer, R.E. & DaPra, C.S. (2012). An embodiment effect in computer-based learning with animated pedagogical agents. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, 239-252.