ATD Blog

Science of Learning 101: 6 Ways to Remove Pointless (but Painful) Effort From Instruction

Thu Aug 18 2016

During the past few months, I’ve been discussing two issues central to the role of organizational learning and development: expertise and cognitive load.

Expertise building is the reason we DO organizational learning, because when people are more proficient at their jobs, they are more able to support organizational goals. People who are less proficient are not only less able to support goals, they can actually cause problems—unhappy customers, errors, or even detrimental working conditions. One of our main roles as L&D practitioners, as I see it, is to reduce time-to-proficiency. In other words, how soon someone reaches the point of proficiency. (Although, I wonder if other L&D practitioners feel similarly—because I haven’t seen organizational metrics measuring time-to-proficiency. More on this in a future post.)

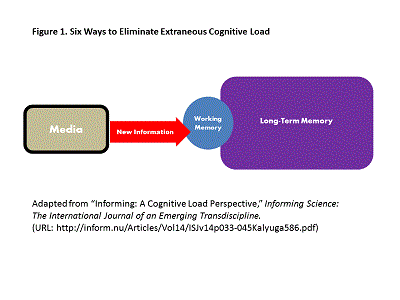

Cognitive load refers to limits on mental processing that affect how much and how quickly people can process new information. As you can see Figure 1, information must be processed first by working memory (WM), which is strictly limited in the amount of information it can process at a time. Long-term memory (LTM) is not limited in these ways, but it takes practice and effort to get new information to long-term memory and organized with prior knowledge.

Some L&D experts contend that instruction is often designed for forgetting, not for long-term memory and application. I doubt that this is done purposely, but it happens because people don’t know how to design for remembering and application. As learning practitioners, we should build instruction using cognitive load principles, so people can learn more easily and more quickly work towards higher levels of proficiency. The first way to use these principles is to eliminate the type of cognitive load that get in the way of learning. That is what I’ll concentrate on for the rest of this post.

**

Six Ways to Eliminate Extraneous Cognitive Load

**

As I said in last month’s post on cognitive load, which means mental effort, cognitive load is additive. Total cognitive load is a result of all three types (intrinsic, germane, extraneous) adding together. If there too much, it’s hard or impossible to learn. But the first two types are needed!

Extraneous load doesn’t add to learning, so it should be eliminated to leave room for the other two. By eliminating it, we actually make it easier to learn.

Research by Kalyuga and Mayer and Moreno tell us how we can decrease extraneous cognitive load situations during instruction. I put some of their main insights into the table below so you can easily use them in your everyday practice.

6 Extraneous Cognitive Load Situations | Description | How can we fix it? |

Associatedinformation elements are separated | Information elements that go together sometimes get separated by location (image on one page and explanation of image on another, legend detached from chart) or time (diagram presented now and audio description presented later). When this occurs, people have to try to hold the separated pieces of information in working memory. | Unite related information pieces to reduce the mental effort of processing them.

Put explanations together with what they are explaining in space and time.

Put data or words corresponding to parts of graphics next to the parts to reduce visual scanning (spatial contiguity effect). |

Related information disappears | Information disappears on one screen before it can be connected with related information on another screen. This requires people to hold information in working memory until the related information appears. | Unite related information on the same screen to reduce the mental effort of processing them. |

Too much visual processing | A graphic or animation has a text explanation. People must visually scan back and forth between the graphic or animation and the text explanation and hold one or the other in working memory. | Present the explanation in narration rather text. Now both can be processed together(modality effect). |

Information is too lengthy | Lengthy new information is hard to process and puts a burden on working memory. | Pre-train necessary prior knowledge such as definitions and facts (pre-training effect).

Segment lengthy, related chunks into smaller, related chunks. (Segmentation effect) |

Information moves too quickly | Quickly moving information is hard to process.

| Provide controls (start/stop) so people can start and stop as needed (part of segmentation effect). |

Extra content | Extra content is provided “just in case,” “just for fun,” or to be “thorough.” Too much processing occurs because there is extra but not needed content. | Eliminate extra material so people can use mental processing for intrinsic and germane cognitive load, which help learning (coherence effect). |

|

There are more insights from the research. In future posts, I will review more extraneous cognitive load situations L&D can eliminate. Also, it’s important to realize that these apply more or differently for people with more domain knowledge, so I’ll look at differences between how we should design for people with more and less domain knowledge.

I’d love to know how you can use these research-based principles in your instructional content. If you are willing to share, it will help other people.

References

Kalyuga, S. (2011). Informing: A cognitive load perspective. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 14.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52.

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4, 295–312.