ATD Blog

The Release of Human Greatness: An Evolution of Talent Development

Thu Jul 26 2018

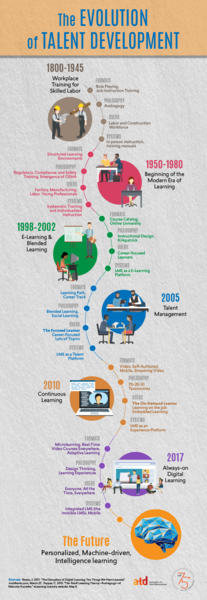

As ATD celebrates its 75th anniversary, I’ve been digging through a lot of our history files to find some gems to share. We have a rich history of helping develop the knowledge and skills of those who train, educate, and develop others in the workplace. But what is the history of the talent development (TD) profession? How did we get here? And what can we learn from history that will help prepare us for the future challenges that are coming faster than we can imagine?

“As man invented tools, weapons, clothing, shelter, and language, the need for training became an essential ingredient in the march for civilization,” wrote Cloyd S. Steinmetz in “The History of Training,” the first chapter in the Training and Development Handbook: A Guide to Human Resource Development, 2nd Edition, sponsored by ATD (then ASTD). He continued, “ . . . man had the ability to pass on to others the knowledge and skill gained in mastering circumstances. This was done by deliberate example, by signs, and by word.”

Training, it seems, has been around nearly as long as people have. And while we have more tools and technology at our disposal, we are still using example, signs, and words to grow knowledge and skills.

Steinmetz, whose work was published in 1976, could have been writing about today when he observed:

Technical and mechanical inquisitiveness took a tremendous spurt after 1750, resulting in the doubling of human knowledge in only 150 years—to about 1900. In the next fifty years, by 1950, it doubled again! The single decade of the 50s witnessed the firing of the technological rocket, and again our sum knowledge doubled. But now a new problem has arisen. The “fallout” of information no longer valid or pertinent has grown to threatening proportions. The seriousness of the situation is further accentuated by the fact that another doubling of total human knowledge is estimated to have occurred in the five-year period ending in 1964. The rapidity of change has become a dramatic challenge to training—a challenge of both addition and subtraction. (emphasis added)

Steinmetz wrote his contribution to the handbook well before the adoption of computer-based training (CBT), the Internet age, or mobile devices. And yet his words ring exceptionally true today. The rapidity of change has become a dramatic challenge to talent development.

In his thorough account, Steinmetz notes particular milestones on the timeline of our profession.

Apprenticeship: Without literacy, the only way to transmit skills and knowledge was direct instruction. “Provisions for governing apprenticeship were instituted as early as 2100 BC, when such rules and procedures were included in the Code of Hammurabi.”

Guilds: These associations of people with shared interests or pursuits helped establish quality standards of products through workmanship. Three levels of guild members were master workers, journeymen, and apprentices.

Craft Training: Early seeds of vocational education showed up in the form of craft training, specifically in gardening and carpentry. “As early as 1745, the Moravian brothers established such training at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.”

Industrial Age: The dawn of the Industrial Age saw creativity flourish and factories arise in impressive numbers. More formal training took root and growth was substantial. As early as 1809 there were vocational training facilities in New York. The Ohio Mechanics Institute was formed in 1828.

Factory Schools: Hoe and Company established the first factory school in 1872 to train machinists. The idea took root and many manufacturers followed suit. The YMCA became an influencer, too, by offering trade training. Another innovation in the first decade of the 20th century was the introduction of cooperative education by the University of Cincinnati’s College of Engineering.

World War II and the Training Director: The ramp-up of industrial production demanded by the War Production Board in the United States put training in the spotlight, and the need for training directors to lead the effort became paramount. The focus on training was so significant that within the War Production Board there was an organization called the Training Within Industry group. Training techniques that were refined in crisis situations during World War I were put into use and industrial training programs flourished.

1950s–1970s: In the 1950s, many high schools began to incorporate vocational education into their curriculums. At the same time, business education was becoming well established in universities. In the 1970s, with regulatory agencies, like OSHA, on the rise, training in the workplace became increasingly important. Instruction was still largely in the classroom or on-the-job (OJT), but some technologies, like audio tapes, were being used. In fact, Cloyd Steinmetz, who worked for many years as the director of sales training at Reynolds Metals Company and Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corporation, was an innovator in the use of voice recording as a supervisory development tool.

In the ASTD Handbook: The Definitive Reference for Training & Development, 2nd Edition (2014), Kevin Oakes updated the history of the profession with a current look that refreshes Steinmetz’s work and provides information about more recent history.

He notes several additional milestones, which include:

1960s: This decade saw a broadening of responsibilities for trainers, the introduction of the measurement of learning effectiveness and the need to understand the business, the adoption of organization development, and the introduction of human performance improvement or human performance technology.

1970s: This decade was marked by an increased understanding that social and technical factors impact an organization’s function. It also saw the rise of sensitivity training and the emergence of case studies used in training to explore topics. At this time, adult learning theory matured with Malcolm Knowles’ book, The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species.

1980s: Global competition became the biggest business challenge, and the ROI for training was in the spotlight. The 80s saw a focus on competencies for the field emerge. The first electronic workstations came on the market in 1981, and using multimedia in training became popular.

1990s: The explosion of technology and e-learning, computer-based training, and online learning increased in popularity and in the TD field. Technology-enabled performance support became more integrated into work, and the concept of the “learning enterprise” was introduced.

It’s stunning to think about the evolution of the profession since just the 1970s, especially in terms of technology. Yet, how we conceptualize talent development has also evolved. No longer merely focused on training for skill acquisition, now consideration must be given to partnering with businesses to deliver impact. Measuring and evaluating impact is a must-do to make a meaningful business case for the real value of investing in people. And, with a workforce more diverse and dispersed than any time in history, intentionality in the design of learning programs is paramount.

What does the future hold? We know it includes virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, at least. And we know these are already transforming the work of talent development. “The rapidity of change has become a dramatic challenge to training—a challenge of both addition and subtraction,” Steinmetz wrote prophetically decades ago.

He also wrote this in closing his chapter on the history of training:

"One thing is certain: Dynamic development forces are needed now and will be needed even more in the future. They will be forthcoming to serve the needs of minorities, including older persons and the handicapped, and to provide for equal opportunity and nondiscriminatory treatment. Such social growth factors are among our greatest assets and are needed in the release of human greatness."

Those words ring true today.