ATD Blog

Leveraging Principles of Art Theory for Visual Design

Mon Jan 04 2021

You want your learners to buy into your training. You must convince learners that they need this information, and that their lives or careers will be better because of it.

But here’s an uncomfortable truth: Your learners silently (if you’re lucky) evaluate the credibility of your work based on how it looks, and they do so with staggering speed. According to UX magazine, people tend to judge the quality of a product within just 50 milliseconds of looking at it.

Of course, a slick PowerPoint deck alone isn’t enough to achieve learning objectives; we know that the principles of instructional design are the foundation of our work. However, quality visual design helps learners appreciate, engage with, and understand your content. Form must meet function for the most effective learning outcomes.

So, how do we create compelling visual designs, especially when we don’t have a background in art?

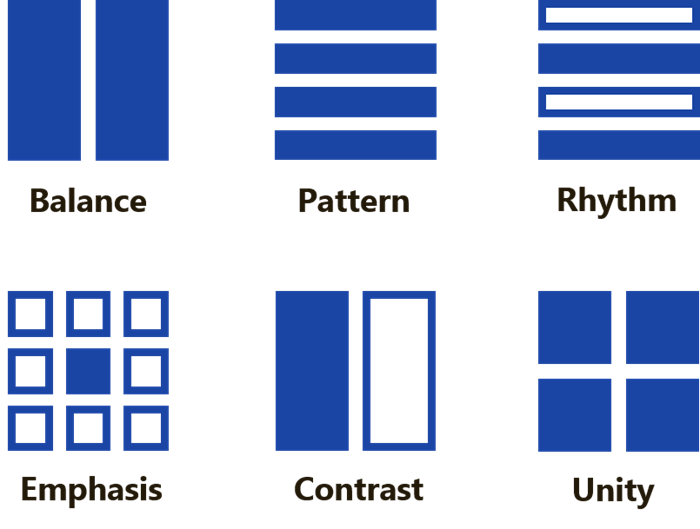

Start with the six principles of design: balance, pattern, rhythm, emphasis, contrast, and unity. Just as instructional design models and methodologies shape your training strategy, so should these principles shape your basic visual strategy. By applying them, you can create high-impact visuals. In addition, the principles provide you with more precise language to critique visual design when it’s presented to you.

The six principles of design are:

Balance: How visual elements are distributed in relation to an axis

Pattern: How visual elements repeat to create consistency

Rhythm: How visual elements repeat or alternate to create interest

Emphasis: How visual elements work together to create a focal point

Contrast: How visual elements oppose each other to highlight differences

Unity: How visual elements create an overall sense of cohesion

To understand how these principles are applied with maximum impact, look to the masters. Throughout history, the world’s greatest artists have used the six principles of design to captivate viewers.

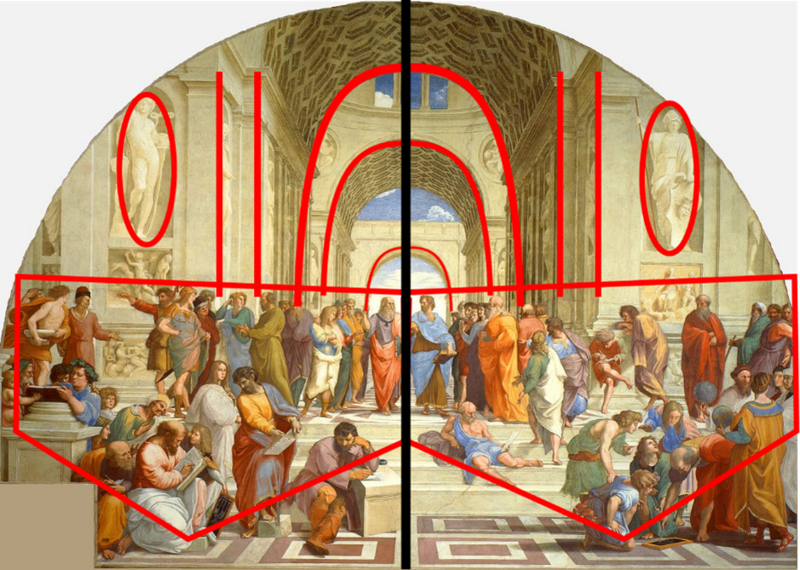

For example, take a look at "The School of Athens,” a fresco by Raphael.

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, The School of Athens, 1509–1511, fresco at the Raphael Rooms, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City. Public Domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

Here, Raphael uses the design principle of balance. Despite not being perfectly symmetrical, all the elements are arranged so that neither the left nor the right side of the work has dominance over the other. We see this when we highlight the major elements (red), in relation to a vertical axis (black):

On either side of the vertical axis, the arches present mirror images of each other, columns are evenly distributed, a marble sculpture appears near the outer edges, and the many figures in the bottom half of the work occupy roughly the same size and shape of space. Using balance, Raphael depicts a large number of elements with a wide variety of colors, shapes, and sizes, without seeming cluttered or disorderly.

Now, here’s an example of how to translate this principle to visual design in a corporate setting.

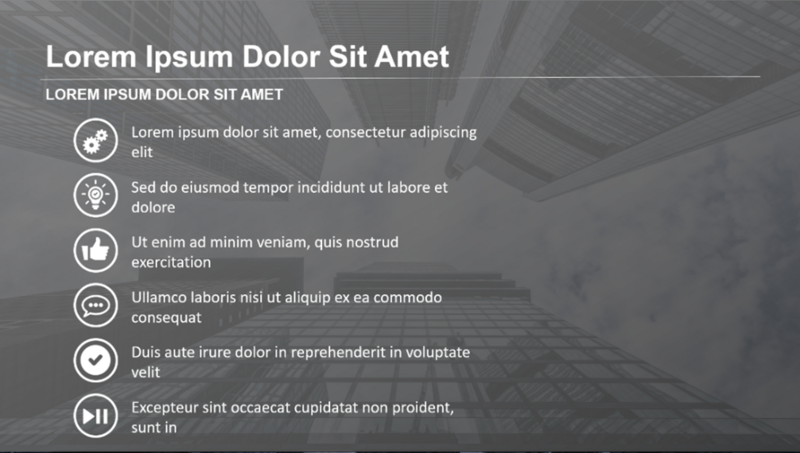

This slide exhibits poor balance in the main body section:

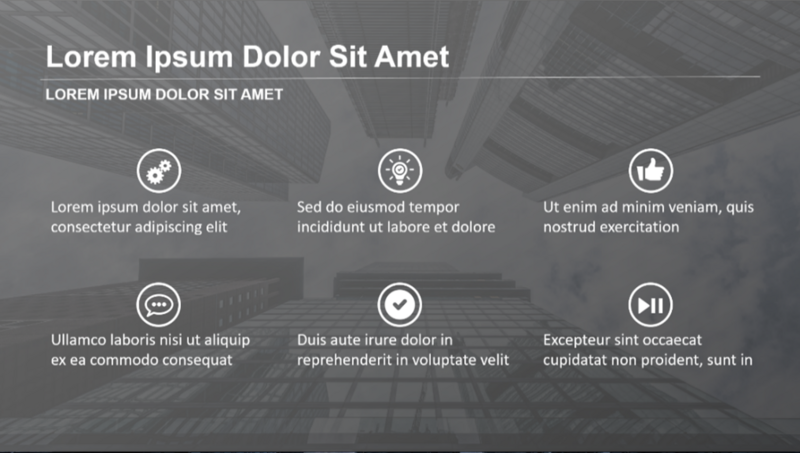

Using the same elements, the main body of the slide can be reconfigured to show balance according to a vertical axis:

But that’s just applying one design principle! Do you want to learn how to apply all six principles to your work, or how to give more precise feedback to your designers? Join me at ATD TechKnowledge 2021 for my session: “Leveraging Principles of Art Theory and History for Visual Design.”