ATD Blog

Science of Learning 101: The Case for Less…Generally

Thu Apr 09 2015

Content

One of the issues to consider when designing instruction is how much instruction to provide. This question isn’t always considered, though, and we either provide too much instruction (or not enough).

One of the issues to consider when designing instruction is how much instruction to provide. This question isn’t always considered, though, and we either provide too much instruction (or not enough).

Content

This brief story will emphasize one aspect of this problem.

This brief story will emphasize one aspect of this problem.

Content

Joanna, a new hire in food service at the local hospital, is using an online course in hand washing. The course contains key facts about germs and how hand washing destroys them, but also statistics about hand washing, facts about different types of hand sanitizers, and the history of hospital-acquired infections and how they spread.

Joanna, a new hire in food service at the local hospital, is using an online course in hand washing. The course contains key facts about germs and how hand washing destroys them, but also statistics about hand washing, facts about different types of hand sanitizers, and the history of hospital-acquired infections and how they spread.

Content

The primary message is that feces contains life-threatening germs and that tiny amounts often get onto hands after using the bathroom or handling objects that others have touched. People in the hospital often have compromised immune systems and if they come into contact with these germs, they can get very sick or die. Hand washing can prevent spread of these germs.

The primary message is that feces contains life-threatening germs and that tiny amounts often get onto hands after using the bathroom or handling objects that others have touched. People in the hospital often have compromised immune systems and if they come into contact with these germs, they can get very sick or die. Hand washing can prevent spread of these germs.

Content

The problem: There is so much other information in the course that Joanna doesn’t get the seriousness of the message. She mostly comes away understanding that it’s a “very old issue.” Joanna passes the quiz but misses the critical message.

The problem: There is so much other information in the course that Joanna doesn’t get the seriousness of the message. She mostly comes away understanding that it’s a “very old issue.” Joanna passes the quiz but misses the critical message.

Content

Consider people handling the following work tasks:

Consider people handling the following work tasks:

Content

Situation A: an accounting clerk in an accounts payable department has a vendor on the phone with a question she doesn’t know the answer to

Situation A: an accounting clerk in an accounts payable department has a vendor on the phone with a question she doesn’t know the answer to

Content

Situation B: an armed guard at secure military facility gate is talking to a driver who is acting aggressively and trying to hand him a wrapped package to deliver

Situation B: an armed guard at secure military facility gate is talking to a driver who is acting aggressively and trying to hand him a wrapped package to deliver

Content

Situation C: an air traffic controller sees two planes on the screen who will shortly be in each other’s air space.

Situation C: an air traffic controller sees two planes on the screen who will shortly be in each other’s air space.

Content

We often build training as if everyone needs to know everything about everything. And it’s easy to overload working memory and make it so people learn less than we want them to.

We often build training as if everyone needs to know everything about everything. And it’s easy to overload working memory and make it so people learn less than we want them to.

Content

We say it’s the SMEs fault. They gave us too much content. But that’s like saying a poor building design is the architect’s fault. Oops it is! And in this case we are the architect. We need to make sure people learn what we need them to learn.

We say it’s the SMEs fault. They gave us too much content. But that’s like saying a poor building design is the architect’s fault. Oops it is! And in this case we are the architect. We need to make sure people learn what we need them to learn.

Content

Cognitive Overload

Cognitive Overload

Content

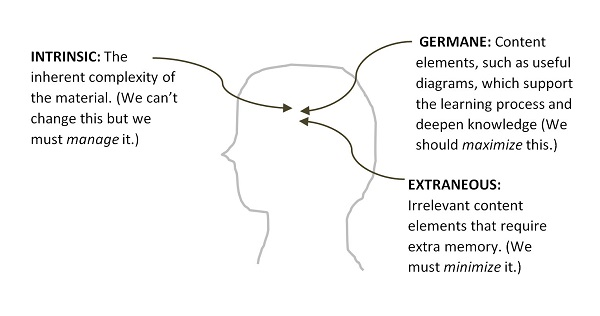

One reason why we need to provide only what people need is explained by “Cognitive Load Theory.” Cognitive load theory states that we have mental “bandwidth” restrictions. In other words, our brain can only process a certain amount of information at a time. And one of the things that can cause overload is too much information. Figure 1 is a diagram that shows the three types of cognitive load.

One reason why we need to provide only what people need is explained by “Cognitive Load Theory.” Cognitive load theory states that we have mental “bandwidth” restrictions. In other words, our brain can only process a certain amount of information at a time. And one of the things that can cause overload is too much information. Figure 1 is a diagram that shows the three types of cognitive load.

Content

Figure 1. Three Types of Cognitive Load

Figure 1. Three Types of Cognitive Load

Content

(Source: Patti Shank and Cecelia Munzenmaier, Writing Better Learning Content )

(Source: Patti Shank and Cecelia Munzenmaier, Writing Better Learning Content)

Content

When Learners Don’t Need to Know Everything

When Learners Don’t Need to Know Everything

Content

Do we need to train the accounting clerk in situation A on every answer to every possible vendor question? Probably not. For that matter, why shouldn’t we train everyone on everything?

Do we need to train the accounting clerk in situation A on every answer to every possible vendor question? Probably not. For that matter, why shouldn’t we train everyone on everything?

Content

People don’t have unlimited time.

People don’t have unlimited time.

Content

The important information will be drowned out by the “just-in-case” information. See the example of Joanne’s hand-washing training. And no, it’s not because they remember 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear …

The important information will be drowned out by the “just-in-case” information. See the example of Joanne’s hand-washing training. And no, it’s not because they remember 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear…

Content

If there’s too much information, it’s easy to get overwhelmed (see Cognitive Overload section).

If there’s too much information, it’s easy to get overwhelmed (see Cognitive Overload section).

Content

I hear you asking, “Where will they get other information if they need it?” This may be non-obvious, but they’re probably not going to go open their previous training materials to find the answers they need. So build performance support materials (or have them do it). Let people get help from their social network.

I hear you asking, “Where will they get other information if they need it?” This may be non-obvious, but they’re probably not going to go open their previous training materials to find the answers they need. So build performance support materials (or have them do it). Let people get help from their social network.

Content

But Some Workers Do Need to Know Everything

But Some Workers Do Need to Know Everything

Content

On the other hand, the workers facing the issues in B and C don’t have time to look up or ask someone the proper response. They need to know what to do in these situations, and how to do it effortlessly--even if these situations don’t happen very often. We call this “automaticity.”

On the other hand, the workers facing the issues in B and C don’t have time to look up or ask someone the proper response. They need to know what to do in these situations, and how to do it effortlessly--even if these situations don’t happen very often. We call this “automaticity.”

Content

Automaticity is the ability to do a task effortlessly without any conscious effort or attention. Making something automatic includes accuracy and speed. Automaticity frees the mind to do other things, such as assess the situation, determine what is important, and find alternatives. Benefits of automaticity seem to be consistent across cognitive, perceptual, and motor tasks. But methods for training to automaticity for these different types of tasks are different (see resources). And training to automaticity requires a lot of work for the training designer and the learner.

Automaticity is the ability to do a task effortlessly without any conscious effort or attention. Making something automatic includes accuracy and speed. Automaticity frees the mind to do other things, such as assess the situation, determine what is important, and find alternatives. Benefits of automaticity seem to be consistent across cognitive, perceptual, and motor tasks. But methods for training to automaticity for these different types of tasks are different (see resources). And training to automaticity requires a lot of work for the training designer and the learner.

Content

We make fun of rote learning, but in some cases, it’s required—especially when dealing with the need for automaticity. The alphabet is an example of where rote learning is required in order to move on to more rote learning for reading proficiency and fluency.

We make fun of rote learning, but in some cases, it’s required—especially when dealing with the need for automaticity. The alphabet is an example of where rote learning is required in order to move on to more rote learning for reading proficiency and fluency.

Content

Not many tasks require the kind of automaticity described in examples B and C, but many do require the capability to recall information quickly, such as answering guest questions at a hotel desk while others are waiting or medical staff helping patients and families during pivotal moments.

Not many tasks require the kind of automaticity described in examples B and C, but many do require the capability to recall information quickly, such as answering guest questions at a hotel desk while others are waiting or medical staff helping patients and families during pivotal moments.

Content

Imogen Casebourne wrote a good Science of Learning blog post about supporting the learning and remembering of this type of information.

Imogen Casebourne wrote a good Science of Learning blog post about supporting the learning and remembering of this type of information.

Content

Key Point: If the task doesn’t require quick recall or the worker has time to look it up, it may be a waste of training time to add the additional recall practice.

Key Point: If the task doesn’t require quick recall or the worker has time to look it up, it may be a waste of training time to add the additional recall practice.

Content

References

References

Content

Thalheimer, W. (March 12, 2015) Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read , ATD Science of Learning Blog.

Thalheimer, W. (March 12, 2015) Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read, ATD Science of Learning Blog.

Content

Holt, B., & Rainey, S., (April 2002). An Overview of Automaticity and Implications for Training the Thinking Process, Western Kentucky University.

Holt, B., & Rainey, S., (April 2002). An Overview of Automaticity and Implications for Training the Thinking Process, Western Kentucky University.

Content

Casebourne, I. (January 27, 2015). Spaced Learning: An Approach to Minimize the Forgetting Curve , ATD Science of Learning Blog

Casebourne, I. (January 27, 2015). Spaced Learning: An Approach to Minimize the Forgetting Curve, ATD Science of Learning Blog