ATD Blog

Why Training Fails By Ann Latham

Wed Oct 02 2013

The main reason training fails is because it isn’t training that is needed. If you want improvement, it is easy to assume the first thing your employee needs is more training. But in many cases, you would be wrong. And when you are wrong, the training you provide will likely be a complete waste. Even when you are right, there are myriad reasons why training has no apparent effect. Training develops skills. While skills are obviously important, skill alone does not enable an employee to succeed.

It’s tough to succeed if you don’t know what you are supposed to do

When a client complained that a supervisor was showing no progress in making improvements in her department, I asked the employee to describe her job responsibilities. She produced a well-organized list of tasks needed to keep things moving day to day. There was nothing on her list to indicate that improving the way her department operated was something she needed to think about.

A new understanding of the scope of her job was a prerequisite for any change. As long as her focus was simply on getting through the day, improvements were unlikely. This may seem an extreme or unusual example, but it is not. One of the biggest complaints in most companies is a lack of communication and that often translates into people not knowing who is supposed to do what when. Only after employees are aware of what is expected of them can you tell whether they have the skills to execute.

Ya gotta wanna

If an employee has no interest in doing what you ask, the clearest expectations and best skills in the world are of little consequence. This happens more often than you might think and it is not just among the punch in, punch out, get paid crowd.

I’ve heard countless managers say that they know exactly what their boss wants, but they have no intention of complying. The reasons include anger and disagreement, more often than inability. They go on their merry way and the boss could easily assume they need training.

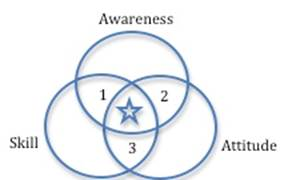

It takes three to tango

The diagram below shows the three components that govern individual behavior: awareness, skill, and attitude. In region 1, an employee is aware that something needs doing and has the skill to do so but not the desire. In region 2, an employee is aware and would like to contribute but doesn’t have the skill to do so. In region 3, an employee would like to help and is able but is unaware of the need. All three are necessary if an employee is to behave as desired.

When looking for a change in behavior, start with awareness. This is often the fastest fix. A simple conversation may do the trick—and listening needs to be a big part of the conversation. “Oh, you mean now!” is emblematic of the kind of revelation that can unlock doors. However, a consistent lack of clarity and communication across people and time can point toward more significant organizational problems and not just issues involving individual awareness.

Assess skill second. While inadequate skills take time to address, it should be pretty easy to distinguish capabilities from awareness and attitude. Could the employee do the task if his life depended on it? I don’t recommend you use threats, but thinking about it this way can help eliminate confusing inadequate skills with problems involving expectations and motivation. If skills are lacking, then training is certainly needed, assuming you have the right person for the job otherwise.

Attitude is the last thing you should worry about. Once an employee knows what is expected and has the appropriate capabilities, a lot of “attitude” problems evaporate.

No man’s an island, especially in the workplace

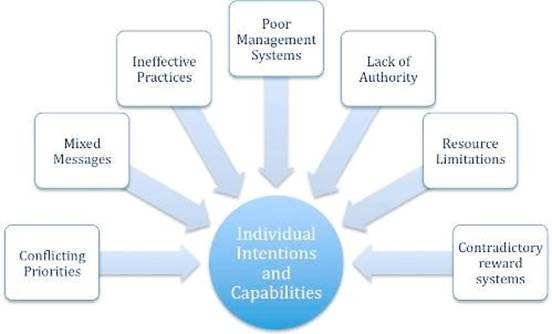

But if attitude still seems to be a problem after ensuring appropriate information and skills, there is still a good chance attitude is not the problem. This is because employees don’t operate in a vacuum. The environment around them provides everything from conflicting priorities and mixed messages to inadequate resources and contradictory reward systems. Most employees come to work eager to do their best and bad attitudes are frequently the result of feeling unable to do their best for any number of reasons. Some of those reasons are shown in the diagram below.

If there are too many priorities, there are no priorities. You can’t just keep adding to an employee’s to-do list. If you want an employee to do something that they aren’t doing, you may need to help them identify things they can stop doing or do more quickly.

Mixed messages are also common. An employee hears one thing, but witnesses contradictory evidence. A classic example involves management harping about quality and then authorizing the shipment of products with known defects. Such action can undo countless efforts to improve quality.

If you talk to employees about their challenges you will often hear them explain that they would like to do things differently and they know their managers want the same thing they do, but current standard practices have them hand-cuffed. A little change here affects the guy next door, the form used, the order of operations, signatures, interfaces between groups, and the next thing you know, the IT department is involved. In short, few processes fall within the control of a single person or even a single group. And few people have the authority, time, or skill set to work though the details and decisions needed to prevent wreaking havoc in redefining the process.

Wishful thinking just doesn’t cut it

Old habits, squeaky wheels, and the path of least resistance have a way of winning. If you expect employees to change their behavior you need to set expectations, ensure they have the skill and support they need, and then hold them accountable.

Are we doing what we said we would do? If not, why not? What must we change? Too often, the management piece of this is ignored. No one is responsible for results. Wishful thinking is not a substitute for management follow-up.

“Employees hate change” is a management cover-up

Something I see frequently at many companies is the employee with lots of ideas for improvement but no authority or access to a mechanism to initiate change. Many would be thrilled if someone would ask their opinions about how things could be improved. Some of these employees manage to push in the right places and get some results; others are eternally frustrated despite their best efforts.

I remember personally attending many meetings where fundamental problems were unearthed, wonderful ideas were formed, and then the conversation and the energy dropped off a cliff while the group struggled to identify a next step—someone to turn to who could make things happen, someone even interested in the problem and the ideas. After a time, those who push for change leave the company or go dormant until something happens to renew their hope and efforts.

Encourage desired behaviors

Resource limitations are related to conflicting priorities. You must support desired behaviors with time, information, tools, equipment, experts, space, agreed methods, etc. You would never expect someone to paint your house with a two-inch brush but the equivalent happens in companies all the time.

“Just do it” is often followed by declined investment requests. While obviously you can’t give everyone everything they want to make their jobs easier, you also need to provide essential support and avoid creating a counter-productive us-versus-them dynamic with your resource allocation process.

Contradictory reward systems can include both official and unofficial reward systems, the former being the compensation system, the latter being the informal recognition. Sometimes both are in conflict with the desired behaviors.

A classic example involves management’s desire to complete projects on time and on budget. They stress planning ahead, meeting deadlines, and anticipating and preventing problems. One project with a dedicated team quietly puts in the long hours, meets their deadlines, and does a great job of meeting expectations. No fuss, no muss, no fanfare. A second project falls behind and gets into hot water.

But then the hero arrives on a white horse and saves the day. Never mind that the hero was part of the team that failed to stay on the straight and narrow in the first place. Who gets all the attention? The acclaim? The bigger raise? If it is the guy in the shining armor, you’ve got a problem. A culture that celebrates fire-fighting produces fire-fighters.

Don’t shoot arrows in the dark

If you want an employee to do his job well, not only must you be sure he has clear expectations, the right skills, and a willingness to do well, you must also be sure the many forces around him are encouraging the desired behaviors and discouraging the undesired behaviors. It may sound overwhelming and financially impossible to get this right. It isn’t. No one gets it “right.” There is no perfect organization.

Success lies in properly diagnosing the hurdles to improved performance in your particular situation. If priorities aren’t really priorities, step back and reassess who you are, where you are going, and how you intend to get there. If your reward system is encouraging the wrong behaviors, change your reward system. If training is needed, train.

If you “fix” the wrong things, you waste money and time. If you “fix” things randomly, the odds are against fixing the right thing. Determine specifically what is preventing the individual and group behaviors that would make a difference in your company. And then remove those obstacles to better performance.

Note: This post is reprinted from the white paper, “Why Training Fails,” © Ann Latham. All rights reserved.