TD Magazine Article

Member Benefit

Give New Life to IDPs

Stem managers’ reluctance to using individual development plans.

Mon Nov 02 2020

Stem managers' reluctance to using individual development plans.

Employers must not give up on individual development plans, especially now. Many studies emphasize the employee benefits of IDPs, but companies should also be mindful of the two main business reasons to use them: to guarantee employees have the skills necessary for today and to ensure the company's future sustainability and growth. By virtue of attending to the business' skill and knowledge needs, employers will also address what employees want—career development.

Why aren't managers developing employees?

Despite the proven importance of development, many managers still do not embrace IDPs—written plans that spell out the expected skills, knowledge, or competencies an employee will need to develop over the next year. Take, for example, this sample of research:

Gartner reports that 70 percent of employees lack the skills needed for today, let alone for the future.

A recent LinkedIn study found that 94 percent of employees would stay longer at their company if their employer invested in their career.

Multiple reports indicate that businesses with strong employee development programs realize higher revenues and shareholder value.

The common reasons managers do not embrace IDPs varies.

Lack of confidence. According to a Gartner survey, 45 percent of managers do not feel confident in their ability to develop employee skills. Indeed, some do not have that ability. Managers also shy away from career discussions because of a misconception that they must have all the answers—for example, that a supervisor must know on the spot the best activities for an employee seeking to learn listening skills or who may serve as the best mentor for a direct report. Authentic managers can simply ask the employee for ideas or come back with suggestions.

Insufficient time and focus. Studies have found that managers lack time to coach their direct reports. And for those who do, Gartner reports that a meager 9 percent of a manager's time is spent in development discussions. Managers are experiencing an incessant pace of disruption, reorganizations, and shrinking resources. Some of that is due to impatience and lack of forethought.

I worked at a company in which leaders frequently restructured organization charts like a bad quarterly habit, spurred by a short-term revenue mentality. Instead of addressing inefficiencies and other OD issues, they performed quick-fix headcount removals. How can anyone focus on employee growth and development in such conditions?

Impractical expectations. Business-minded people under pressure want results now, but employees cannot hurry up and learn. That mindset involves a shortsighted lack of leadership, unrealistic expectations, and deficient appreciation for talent development.

Lack of understanding. There is confusion among employees and managers about the ideas of performance and development. Employees often perceive that there's a performance problem when they hear the words "development plan," and many supervisors believe coaching is only used for managing a performance problem.

In addition, some managers believe a promotion is a form of development, or they fear that in career discussions, employees will expect promotions or raises that they cannot fulfill. So, rather than managing expectations up front, supervisors do not initiate such conversations.

Other managers believe training is development. Their futile approach has been to say, "I'm going to send you to a class" while handing over an IDP form to an employee. Task completed. Box checked. Class not completed.

A complex process. The IDP process has become an arduous chore for managers. Companies have created badgering systems and processes in the attempt to enforce compliance with IDPs. Unfortunately, companies have lost sight of the IDP's original purpose. Processes have advanced from over-engineered paper forms to technical versions of the same. The IDP's goal has evolved to inputting detailed text into the correct field, obtaining approvals by deadline, then receiving the prized automated message of Completed.

Avoiding IDPs is understandable in some cases—they may involve frustrating, time-consuming, tedious processes and systems—but managers' responsibility is to ensure employees are equipped to fulfill their roles and flex with business needs. Not having enough time has turned out to be managers' veiled discomfort with, or a lack of appreciation for, IDPs.

Proposed changes to the process

To develop an IDP, a manager and employee should create it together, typically simultaneously or immediately following the annual performance review. In some cases, plan development can take shape in the latter portion of a performance review form.

To help reluctant managers embrace IDPs, companies can make several adjustments.

Reposition IDPs. Position the plans as one of several talent strategies for business growth and sustainability. The criticality of individual development is more extreme than what employers may have realized on the surface. David Deming is professor of public policy, education, and economics at the Harvard Kennedy School. According to his research, continual evolving adoption of artificial intelligence will replace some jobs but will not replicate certain abilities that only humans possess (for now). For example, there will continue to be an increased need for soft skills, which are irreplaceable by automation.

What employers want are employees who are flexible, adaptable, and skilled at working in team settings. Employees must be empathetic, having the capacity to understand how others are motivated and being able to put themselves in others' place. Staff with strong social skills are more responsive to change and capable of trading tasks with a variety of co-workers. They are adaptable and flexible in a changing work environment, having the ability to take on different roles in different situations.

That does not dismiss the need for hard skills, but it shifts the emphasis. Deming's research is an eye-opener for more laser focus on learning how to learn. With digitalization, globalization, and new generations in the workforce, organizations must be more elastic, powered by agile employees, systems, and processes. The unpredicted impact on how companies do business during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic is confirmation of that reality.

Employees cannot settle into their comfort zones and resist the challenge of newness. Single-skill sets are no longer germane. Rather, a T-shaped strategy—a breadth and depth of skills—is more prudent. Employers should rethink job descriptions to reflect cross-training and rotations that promote a nimble culture and competitive advantage.

Managers should assess their organizations' skill and knowledge gaps first, then determine how to develop their team members' abilities to address those gaps.

Reframe development as a learning process. During onboarding, employers should convey continuous learning as philosophy in practice. Everyone in the company is responsible for promoting such a culture.

What makes someone employable today will not guarantee their employability in the future. Consider job descriptions that could foster limitations to what employees will and will not do. "That's not in my job description" is a phrase that leaders sometimes hear. Although "other duties as assigned" is still a relevant phrase, adding "Remain current with learning requirements" or similar language communicates an expectation of ongoing learning.

Accountability. Managers are responsible for hiring, developing, and retaining talent. A team's performance is reflective of its members and ultimately its leader. Lack of time is not a valid reason for lack of accountability.

To make employee development a priority, managers should carve out the minutes and hours for it. I ask managers how long it takes for a 10-minute check-in with an employee to find out how things are going with a new project. Compare the answer to the length of time it would take to replace and retrain employees who seek careers elsewhere. Clarity of roles in the IDP process can place ownership on the employee to keep their plan alive while the manager supports that individual's learning success.

Update semantics and simplify the structure. People often perceive development as an amorphous term, so replace it with learning. As noted earlier, there is also confusion about the difference between performance and development. "We develop film, not humans," one manager told me. Simply put, development is learning and forward focused; performance reviews reflect. Thus, managers should de-couple performance and development planning discussions.

An IDP is a form, a component of the individual development process, which has become cluttered with the popular SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound) goal format and other details. The structure of SMART goals resonates with managers because it guides them. However, it can have a reversal effect as they and their employees struggle to understand the difference between resources and development activities.

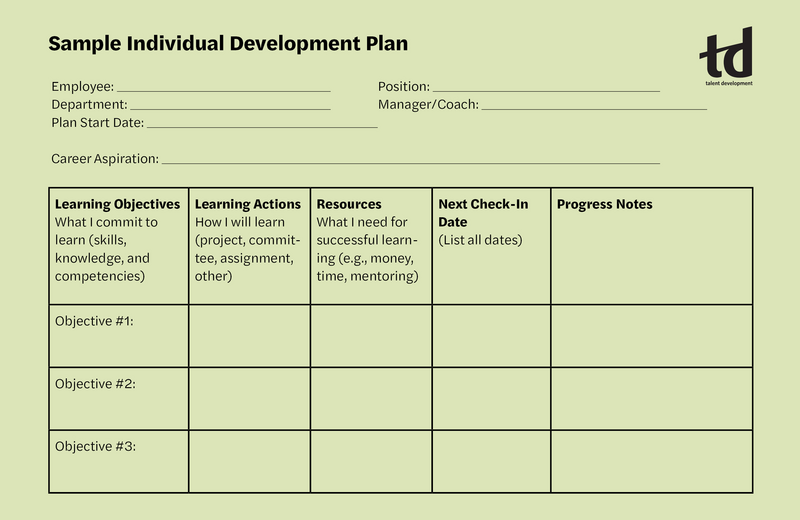

In addition, because learning is ongoing, pinpointing a learning goal's completion date can be difficult. To insist on arbitrary completion dates is absurd. How can learning in a perpetually changing business environment be deemed complete by a particular date? Instead, managers should identify a date for the next goal check-in to discuss progress (see sample IDP).

Engage in robust career and learning discussions. Having meaningful career conversations is the most important element of the individual development process. An employee and manager have a dual opportunity to make the most out of a career discussion. Both parties should come to the discussion prepared to engage in dialogue with a productive positive mindset (see Four-Step IDP Process for Managers).

Supervisors should review in advance the organizational imperatives, the skill needs for their teams, and potential learning options for the employee. They also should be prepared with several questions to encourage the employee's openness and input (see Career and Learning Discussion Facilitation Questions). They should think of ideas and perspectives during the discussion but allow plenty of dialogue space to collaborate on a plan. Likewise, employees should be prepared to discuss their career aspirations, strengths, areas of learning potential, and interests.

Managers should transcribe the discussion's outcomes into an IDP or another note-taking format to capture in writing the learning goals, next steps, and next check-in. They could then use the draft IDP as foundation for a concise plan born out of valuable dialogue with their direct reports.

Support managers. Nobody is born knowing how to have career and development conversations. Thus, the talent development team should plan well-designed workshops to provide managers with a forum for practicing career discussions and creating draft IDPs.

Managers should rest assured that they do not need to have all the answers. Thoughtful questions can facilitate meaningful discussions with employees. The goal is to have discovery discussions that align employer and employee needs, not "We need to fill this form out."

Creative learning practices

Part of making IDPs relevant is an organization having a culture of learning, offering practical and rich learning experiences. Here are a few creative approaches companies have used to address business and employee needs:

Google implemented Career Guru, which provides employees one-on-one coaching from seasoned Googlers globally. Coaching conversations range from innovation and leadership to presentation skills and team development.

At Southwest Airlines, Days in The Field enables associates to discover new career paths by rotating through a department that interests them.

Consulting firm Bridgespan ensures that every day is different for employees as they take on versatile roles, using varied skills to accomplish challenging tasks. That in turn cultivates an agile culture, ever ready for change.

At eMarketer, continuous learning is embedded in its culture. Reading is essential to remain competitive as a go-to company for digital expertise. Thus, the CEO shares recommended books and business bestsellers for team inspiration.

Every week, TripleLift holds a Tech Trek during which employees share with their colleagues projects they are working on. That provides a forum for employees to have constant access to new information and for teachers to become subject matter experts.

HBO encourages employees to take educational field trips with their co-workers to learn about new technologies.

Learning's relevance in business is more imperative than ever, not only because employees want it but because it is necessary to match the ongoing transformation in global businesses. The process must be simple, creative, and experience-based, with high impact and always ready for another change. Companies should be vigilant about keeping the primary emphasis on employees and managers learning how to have a learning dialogue and less about re-engineering a form that has lost its way.

Four-Step IDP Process for Managers

Step 1: Prepare

Understand the intention and desired outcomes of a career and learning discussion.

Review organizational goals, priorities, and associated new skill requirements for your team.

Send thoughtful questions to the employee before the career discussion.

Adopt a positive mindset.

Consider possible assignments, projects, committees, delegation, and mentor opportunities.

Determine whether there are any anticipated challenges to the conversation—for example, a quiet employee, being unfamiliar with L&D, unsure of career aspirations, unrealistic expectations.

Be prepared to position the discussion's purpose to manage expectations.

Step 2: Discuss

Set the tone for a positive discussion.

Explain that this is not about title, compensation changes, or performance; it is about supporting the employee's career and learning.

Ask questions, with the employee doing most of the talking.

Use probing, follow-up questions to gain a deeper understanding of the employee's career and learning interests.

Offer ideas only after the employee has shared theirs.

Discuss the concepts of the comfort zone (where most employees operate daily in terms of the skills, knowledge, and environment where they are most comfortable) and the learning zone (where employees take risks in new experiences to learn and grow) to provide context for learning on the job.

Test your assumptions. Do not assume to know the employee's career aspirations, because they may change over time.

Use the conversation's outcome to feed the learning plan.

Step 3: Write

Encourage the employee to take notes. Use a learning plan template as a guide.

Your note-taking also reinforces that what the employee is telling you is important and that you are listening.

Clarify your and the employee's roles in maintaining the plan going forward.

Request employee follow-up with a capture of the conversation in the form of a draft plan, and schedule a first check-in.

Step 4: Follow up

Review the employee's draft plan to ensure you are both aligned.

Express confidence and support for the employee.

Keep learning alive with brief check-ins. They can be informal updates of at least 10 minutes to review progress on learning and address any obstacles.

Emphasis should not be on filling out a form but rather on having a deep, meaningful career discussion that aligns with employee and employer needs.

Career and Learning Discussion Facilitation Questions

Managers can use these facilitative questions to make the most of a career conversation with direct reports.

Starters and prompts

What are your short- and long-term career goals?

How does your work here fit in with your career aspirations?

Tell me about a day at work that you would characterize as a great day. What made it a great day? What were you working on?

What or who supports you in your best work?

Do you know our division's or unit's goals and the company's goals for this year?

How do you see yourself contributing? Do you feel you have the skills and knowledge for your part?

What work skills and talents do you have that I may not know about?

What skills and talents do you feel are not being tapped?

What motivates you the most at work?

Do you have a mentor?

What kind of work or activities would be more motivating, interesting, or intriguing to you?

What projects, committees, or other initiatives would be of interest to develop your career?

What else do you want to learn?

Goals

How could you learn those objectives?

Which are most intriguing to you?

Based on our discussion, what do you want to learn this year?

What learning objectives are you willing to commit to?

What experiences could help you progress toward your career goals?

What do you need from me to support you in this project, committee, or assignment?

Progress

When would you like to have our first progress check-in? It can be 10 minutes or more.

How is your learning plan coming along?

What's working and not working?

Is anything getting in the way of your success?

What's helping your success?