TD Magazine Article

Healthcare Workers Seek Infusion of Positive Workplace Culture

Unique aspects of the healthcare industry present challenges to organizations seeking to increase satisfaction and well-being among clinicians.

Fri Mar 01 2024

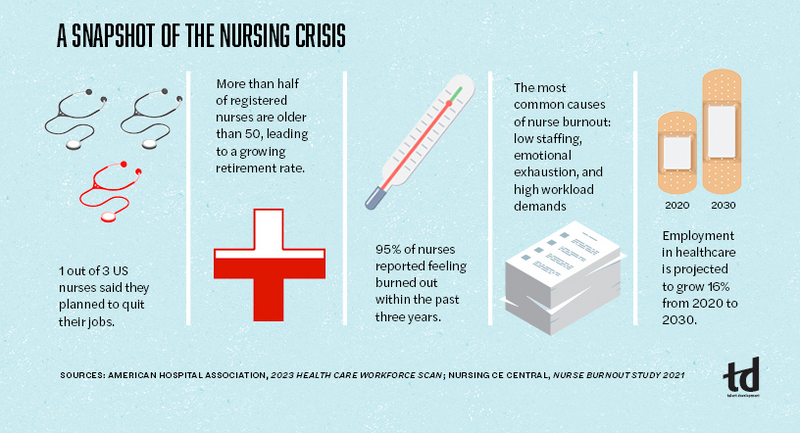

Healthcare workers have certainly been taxed in recent years. That strain, according to an AMN Healthcare survey, is leading workers—especially younger nurses—to leave the profession in droves. Pandemic-related stress, nurse shortages, burnout, and workplace culture are a few of the factors.

In an interview on HIMSS TV, Shafi Ahmed, chief medical officer at virtual reality education company Medical Realities, offers ideas on how to address the dissatisfaction and shortage of healthcare professionals. Among the suggestions he shares with the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society's online broadcast network is a healthcare model similar to the technology industry that allows healthcare workers to spend part of their workweek on alternative endeavors such as innovating solutions for their teams.

Another option is to allow healthcare workers to pursue parallel careers, splitting their professional work time—for example, practicing 20 hours per week and teaching or operating a business during the other 20 hours. To shift away from what Ahmed says is still a traditional healthcare field, he advises using more career mapping, which he suggests will alleviate staff becoming jaded and bored with their roles.

Many healthcare organizations are taking steps to increase clinician well-being and satisfaction by leveraging some of the very things Ahmed mentions. Talent development professionals are well positioned to be involved, and it starts by listening to staff.

How is healthcare different?

On the surface, many healthcare workforce challenges seem universal and, indeed, there are commonalities. However, apart from the distinct issues healthcare professionals faced during the height of the pandemic, there is often a lack of flexibility for many nurses both in terms of scheduling—numerous facilities continue to adhere to 12-hour shifts—and work location. That means nurses and other health professionals are missing out on the flexibility that countless workers have come to enjoy during the past four years.

The healthcare industry likewise is experiencing an increased incidence of patient violence on nurses and other caregivers, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and data from the National Nurses United. That hostility may result from a patient receiving a negative diagnosis, bad news about a loved one, or what families or patients see as inadequate care.

The practice of traveling nurses can also be a cause of consternation in hospitals and medical offices. While travel nurses may alleviate staff shortages, they earn more than staff nurses, and—per MIT Sloan—may feel heard by the staffing agency to a greater degree than staff nurses do by their managers or HR. Further, nurses have historically experienced dissatisfaction with the facility hierarchy—disrespected by doctors and administrators, many of whom believe they are superior to nurses due to their education and title.

Engaging staff to find and address pain points

The TD function can be instrumental in addressing workplace culture that is at the root of much of the dissatisfaction among nurses and other clinical staff. As with other industries, managers are key to listening and providing feedback to nurses, which enables them to feel heard and valued.

TD professionals can help by providing templates, facilitating stay interviews, practicing role modeling, and instructing on the importance of emotional intelligence, for example. Further, talent developers can contribute to employee engagement surveys and ensure their leaders act upon the results, even if it is to report that the organization can't fully institute certain sought-after initiatives at that time.

Stretched to the limit

An obvious pain point is overly stretched staff. In the Committee for Economic Development's (CED) Policy Watch webinar,"Health Policy After the Pandemic," among the topics a panel of experts address is workforce issues. The CED is the public policy center of the Conference Board. Ashish K. Jha, former White House COVID-19 response coordinator and dean of Brown University's School of Public Health, comments that as a society, the US must re-evaluate the roles of healthcare professionals—for example, by being flexible about "scopes of practice." Technology "enables people to do different jobs than they could do 10 or 15 years ago," Jha continues. Telemedicine is one avenue to offer healthcare delivery more efficiently.

Healthcare roles is also a matter raised by Terry Shaw, president and CEO of AdventHealth, who notes during the webinar that the US needs to radically rethink nurse extenders and how to use physician assistants.

The Conference Board issued recommended pathways forward in a report by the same name as the webinar, which included "expanding training and professional development opportunities" to encourage retention as well as offering apprenticeships. Further, team-based care "will help ensure that all health care workers are practicing ‘at the top of their license.'" Several organizations are leveraging such practices.

Humana's rotation program for nurses

Humana is a Louisville, Kentucky-based, national health and well-being company that has staff working in a variety of settings—in person, hybrid, and remote. Nurses work in various roles across the organization.

Listening to staff was at the heart of creating a rotation program for nurses, explains Kathy Driscoll, Humana's chief nursing officer. Nurses wanted career journeys that would enable them to gain exposure to an array of teams and divisions across the organization. Driscoll says her goal was to "ensure we have a contemporary workforce with contemporary skills, and at the same time, identify skills that are transferrable as healthcare expands and grows."

The chief nursing organization developed the program in tandem with HR; it involves nurses rotating to a new department for six-month periods. Participants immerse themselves in different parts of the healthcare spectrum to learn new skills relevant to that department and the business of healthcare. Rather than serving as clinicians during their rotations, participants work on initiatives the host department has prioritized, such as health equity and community engagement, internal audit consulting, and learning design and facilitation.

Nurses take a lead role on their host team, not just act as a spectator, Driscoll emphasizes. At the same time, the opportunity exposes members of the sponsoring team to what nurses bring to the table besides clinical skills, such as interpersonal behaviors and perspectives—for example, technology usage or the interplay between nurses and patients.

In addition to the knowledge and skills participants develop, they have access to—and managers and HR encourage them to take part in—additional training during the rotation, much of which is virtual instructor-led programming. The coursework includes topics such as writing a resume, interviewing, and learning how to frame the skills they are attaining in their human capital management profiles.

Rotating nurses also have opportunities to hear from HR or other leaders about the business of the organization and its values. The supplemental training to the rotations has become so popular, Driscoll notes, that even nurses who are not participating in the rotation program often sit in on the sessions.

Nurses opt into the rotation program, and the sponsoring team subsequently selects participants based on an application and interview process, with manager approval and involvement. Different teams or business lines advertise a position for the program, including the skills they are looking for and the responsibilities that the rotating nurse would be performing. Nurses will usually choose three different areas they're interested in and go through the interview process.

"We're seeing nurses who never thought they'd be working in fields like digital leadership or informatics," Driscoll explains, "who end up not only doing a rotation in that department but who may ultimately go on to work in that field."

Throughout the program, the sponsoring team, the nurse's "home" team, and Driscoll's chief nursing organization team conduct regular check-ins. The discussions focus on what skills the nurses are developing, for example. At the end of the program, the rotating nurse delivers a capstone presentation to leaders from the sponsoring and originating teams, the talent acquisition team, and other leaders. Often, the sponsoring team leader will attest to the skills and assets the nurse brought to their team.

"We've experienced what is seen more broadly in the nursing field: that nurses don't necessarily want to stay in the same role for 30 years," Driscoll says. She explains that although nurses want more agile and dynamic opportunities, they sometimes aren't sure where exactly they want to grow. The rotation program enables them to network across the organization as well as learn from nurses who have rotational experiences on certain teams.

Organizationally, business lines that never would have considered nurses to fill roles now do, Driscoll states. Some have even created a hybrid role for the clinician skills and business skills that the nurses have developed.

Mary's Center's facilitated telemedicine initiative

As important as it is to develop nurses and other healthcare staff and provide flexibility whenever possible in their scheduling, there's still a significant nursing shortage in many facilities across the US. That's where using technology, providing efficiencies, or tapping alternative forms of staffing—or a combination—can come into play.

The facilitated telemedicine program at Mary's Center in Washington, DC, leverages technology and skilled medical assistants to create staffing efficiencies. The organization trains MAs in phlebotomy (the practice of collecting blood samples) so they can conduct in-home patient appointments, equipped with a high-definition laptop, hot spot, and digital telescope. MAs work with a provider who is connected via video, likely clinic- or home-based, to discuss test results and care with patients as needed.

MAs also receive training on collecting other lab samples, administering vaccines, conducting hearing and other tests, and discussing such topics as fall prevention. Beyond the clinical and technical skills, facilitated telemedicine MAs must have a unique and special aptitude: remaining nonjudgmental about a patient's environment and flexible in tending to their needs when going into the patient's neighborhood and house.

Mary's Center is equipped with a training school, explains Ingrid Andersson, director of care coordination. Among its offerings are in-person and online training courses on communications, equity, domestic violence, and human trafficking recognition, most of which are mandatory for all staff. Additional training—either offered by local partners or conducted by the center's HR/people team—includes topics such as leadership training and coaching; motivational interviewing; and centering facilitated training, another communication technique. The training specifically helps MAs to better interact with patients during visits in the field.

Program participants have a career ladder that begins with MA1 and runs through MA3. MAs who conduct the facilitated telemedicine visits are at the second or third levels. In addition to having attained the prerequisite level of training, admission into the facilitated medicine program requires a letter of recommendation from their supervisor. Candidates shadow an experienced facilitated telemedicine MA before formal admittance to the program to give individuals the opportunity to ascertain whether the role is something they want to pursue.

Once accepted into the program, participants continue to accompany an experienced MA to on-site visits. That generally runs from three to four weeks and is based on feedback from the experienced MA and the program participant's new supervisor.

Although facilitated telemedicine visits do not replace all on-site visits, the program participants create efficiencies and save time from tasks for which nurses may otherwise be responsible. The MAs coordinate care, for example, such as working with insurance companies to determine why they don't cover a particular prescription or to secure care for a patient.

One of the organization's IT staff members works with the facilitated telemedicine team to ensure that the technology the MAs use is correctly configured.

Andersson states that the program has helped break down silos between staff members—with providers learning and appreciating what on-site MAs can share with respect to the patient and their health, and vice versa as the MA and provider have a greater level of interaction. Further, the organization's geriatrician helps train the MAs in identifying cognition, for instance. The geriatrician has shown appreciation for the insights MAs bring as a result of seeing patients in their everyday environment. MAs can also recommend training for providers, mentioning, for example, that a particular provider is adept at some level of interaction and suggesting that provider train others.

A healthy future

The TD profession can help lead the way to a healthier future for healthcare organizations. To have more satisfied employees and to provide better care to their patients, healthcare facilities must change. Workplace culture must adapt to allow for greater multidisciplinary collaboration and communication.

More flexible workforce models that introduce new career pathways allow for not only greater fulfillment but more innovation and creativity. They also instill greater satisfaction in the profession.