The Public Manager Magazine Article

Managing Cross-Sector Collaboration

Mon Dec 15 2014

Cross-sector collaboration (CSC) is becoming a more familiar fixture on the governance landscape. Alliances involving government, business, and nonprofit organizations are now addressing issues that were once viewed as the prerogative of government.

Local healthcare services, foster care and adoptions, safe drinking water and water treatment, homeless shelters, wildfire response and recovery, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, building and improving roads, park maintenance, expanding seaports and building airports: All these and other public goods and services are now delivered through some form of cross-sector collaboration.

Why Cross-Sector Collaboration?

Public managers engage business and nonprofits in CSCs for several reasons. Many governments are facing a budget crunch at the same time that the cost of and demand for public services is on the rise. CSC can be one way to bring additional resources to communities and areas of need.

In addition, many of today's complex problems—childhood obesity, for example—require responses from multiple and interconnected sectors and perspectives. CSC brings together different actors, each with unique expertise, experiences, and vantage points to find solutions to these problems.

Typically, businesses and nonprofits have greater flexibility than government agencies and are positioned to move more quickly and take advantage of emerging opportunities. As a result, CSC allows governments to offer public services that may be more responsive and adaptive to citizens' needs.

For these reasons and others, the practice of CSC is growing and expanding. Public managers are right to raise questions and concerns about their efficacy, but CSCs are growing in popularity and they are here to stay as a tool of governance.

Different CSC Approaches

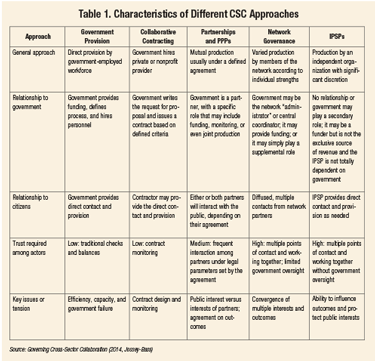

CSCs come in all shapes and sizes and have adapted to the specific conditions found in local communities or state and federal governments. Emerging from the diverse practices are four basic CSC approaches. Each one offers a different set of relationships, expectations, and governance issues that must be managed by public managers.

Collaborative contracting. These "complex" modes of contracting generally adhere to one or more of the following characteristics:

They involve "incomplete" specifications of expectations because the involved parties modify their requirements over the course of the exchange.

They are "relational"—they involve aspects of governance that stretch beyond the formal or written terms of agreement.

They are generally long term in nature and involve frequent interactions of the parties.

Partnerships and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Governments collaborate with businesses or nonprofits in three typical ways:

short-term, one-to-one partnerships for a specific purpose or goal, such as private and public formation of a downtown business district or commercial development, or a partnership between government and a local community organization to fund and equip a local park

intermediate-term partnerships involving government and nonprofit providers, such as a state department of human services or a local shelter for the homeless

long-term partnerships involving the creation or renewal of major infrastructure projects (often termed P3s in North America), which include private financing and operations and maintenance of infrastructure systems and facilities.

Network governance. Collaborative arrangements that involve a broad range of non-governmental stakeholders working interdependently with government. Networks typically organize themselves in three different ways:

shared or self-governed, where network members are collectively involved in their own governance

lead organization, where one entity coordinates the network's operations

network administrative organization, where a designated entity (with designated staff and responsibilities) supports and governs the network's activities.

Independent public-services providers (IPSPs). This emergent form of collaboration is distinctive by not being directed by government officials. Typically funded by foundations, fees, grants, or gifts, it can set its own agenda and select approaches to delivering public services:

PSPs are typically organized as diverse networks, engaging business, nonprofits, and governments to work collaboratively, and undertaking innovations that improve current practices.

IPSPs operate outside the typical bureaucratic and political constraints public managers face every day.

The four different CSC forms offer public managers choices on which approach is best suited to promote the interests and goals of the government program being implemented.

Relationships and Expectations

Each CSC is distinguished by the type of relationship the government has with its collaborators as well as expectations for government's role in the CSC.

Collaborative contracting entails the greatest levels of direction and control provided by the government in the CSC.

PPPs and partnerships allow greater discretion to private and nonprofit partners, and public managers rely more heavily on their partners for guidance on the best approaches to delivering public services.

Network governance involves even more independence by its members. Governments may play a relatively small role in the operations of networks, allowing members to operate and coordinate in a way that has proved to be effective. Governments may guide networks in goal setting and the framing of outcomes, but networks often operate and deliver services outside of day-to-day bureaucratic control or review.

IPSPs are largely autonomous and set their own priorities and agendas. Government agencies may be invited to participate among the other private and nonprofit participants, but they do not select nor veto IPSP activities.

Advantages and Disadvantages

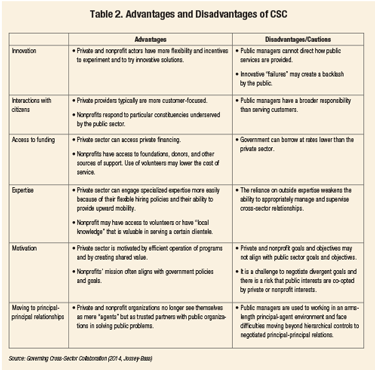

Public managers must choose the nature of their involvement in CSCs carefully. A misunderstanding of reasonable expectations for relationships and responsibilities within CSCs is the greatest threat to their success. When selecting the best type of CSC, public managers need to take account of numerous factors, including:

nature of the public task or challenge

resource needs and capacity

identification and allocation of risk

best value for the public's dollars

measuring performance and ensuring accountability.

Experience suggests that some CSCs are formed with relative ease when interests, needs, timing, and expectations align, such as responses to natural disasters. Others, and particularly those that are engaging collaborators on more challenging issues—such as teenage homelessness and abuse—require a lot of work, patience, and perseverance to come together.

Some CSCs may take several years to mature, learn from their experiences, and reinvent themselves, to find their full potential. Understanding the advantages and disadvantages to governing through CSC is essential for public managers.

Cross-Sector Collaboration and Democratic Accountability

Successful CSCs operate in heterarchies, providing them greater discretion, flexibility, and even autonomy—it allows them to be creative, innovative, and adaptive. Citizens benefit by receiving better public services. Yet this same strength of CSC also raises legitimate concerns over democratic accountability.

To address these concerns, public managers should focus on four "pillars" of democratic accountability:

Agree on clear measures of outcomes.

Create public value.

Promote a trusted partnership.

Increase citizen awareness and engagement (creative uses of social media can help promote these actions in an integrated and highly effective way).

CSC offers novel approaches to governance that can result in dramatic improvements in the delivery of public services in a rapidly changing world. One thing that has not changed is the public manager's responsibility for ensuring that any CSC is undertaken in the public interest.