ATD Blog

How Long to Develop One Hour of Training: A Case Study

Tue Feb 05 2019

Content

It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since I shared the updated numbers for how long it takes to develop one hour of trainin g . Obviously, a lot can happen in a year, but one thing has remained constant: your interest in this topic. Whether it was a request for more research or an inquiry on how to apply the data to their own projects, L&D professionals wanted more insight on training development processes and efficiencies.

It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since I shared the updated numbers for how long it takes to develop one hour of training. Obviously, a lot can happen in a year, but one thing has remained constant: your interest in this topic. Whether it was a request for more research or an inquiry on how to apply the data to their own projects, L&D professionals wanted more insight on training development processes and efficiencies.

Content

Because most of the post-article chatter revolved around limited resources and advocacy, this follow-up reviews how to apply the data to your own work. Before we do that, though, let’s recap some of the highlights from the earlier research.

Because most of the post-article chatter revolved around limited resources and advocacy, this follow-up reviews how to apply the data to your own work. Before we do that, though, let’s recap some of the highlights from the earlier research.

Content

In 2003, Karl Kapp established the initial study. He defined different types of training, including instructor-led training (ILT), e-learning, and simulations, as well as the levels of interaction within the training. The study also accounted for whether training was designed with a template. The data was presented using the average “lowest development hours” and “highest development hours.”

In 2003, Karl Kapp established the initial study. He defined different types of training, including instructor-led training (ILT), e-learning, and simulations, as well as the levels of interaction within the training. The study also accounted for whether training was designed with a template. The data was presented using the average “lowest development hours” and “highest development hours.”

Content

In 2009 , Karl and I expanded that research by considering new authoring tools in the training market like Articulate. Additionally, we examined simulations not only from a hardware standpoint, but also for instructing learners on various issues such as soft skills. Lastly, we asked participants to base their responses on ADDIE principles. In comparison to 2003, the numbers for each category were higher than the original research.

In 2009, Karl and I expanded that research by considering new authoring tools in the training market like Articulate. Additionally, we examined simulations not only from a hardware standpoint, but also for instructing learners on various issues such as soft skills. Lastly, we asked participants to base their responses on ADDIE principles. In comparison to 2003, the numbers for each category were higher than the original research.

Content

Another enhancement to the 2009 study was that it asked for candid insight from participants. This helped us to qualify the increase in development time and develop a baseline understanding of key influencing factors. For example, in different instances, we could attribute the higher numbers to scope creep, lack of comprehension by subject matter experts, or the stakeholder’s role in contributing to project success.

Another enhancement to the 2009 study was that it asked for candid insight from participants. This helped us to qualify the increase in development time and develop a baseline understanding of key influencing factors. For example, in different instances, we could attribute the higher numbers to scope creep, lack of comprehension by subject matter experts, or the stakeholder’s role in contributing to project success.

Content

In 2018 , we reprised the research, redefined the categories of interactions, and simplified the overall survey to just two questions. The numbers fluctuated yet again, with an overall decrease. More importantly, we advocated that folks use the data as a guide and consider other influences. For example, some new considerations were the training developer’s years of experience and the specific training development process used by an organization.

In 2018, we reprised the research, redefined the categories of interactions, and simplified the overall survey to just two questions. The numbers fluctuated yet again, with an overall decrease. More importantly, we advocated that folks use the data as a guide and consider other influences. For example, some new considerations were the training developer’s years of experience and the specific training development process used by an organization.

Case in Point

Content

The efforts of Sandra Colley provide a perfect case for understanding and applying the foundational data presented by the preceding research. As a seasoned training manager at Nationwide Insurance and president of the Society of Insurance Trainers & Educators (SITE), Sandra has a vested interest in serving her organization and the insurance industry. In fact, she zeroed in on how to make the data work for her work at her organization—and her industry.

The efforts of Sandra Colley provide a perfect case for understanding and applying the foundational data presented by the preceding research. As a seasoned training manager at Nationwide Insurance and president of the Society of Insurance Trainers & Educators (SITE), Sandra has a vested interest in serving her organization and the insurance industry. In fact, she zeroed in on how to make the data work for her work at her organization—and her industry.

The Approach

Content

When Sandra took on the training management role, she realized her team lacked a set standard for project timeliness—but needed one. She embarked on her own study to learn how our research data applied to the work happening inside her organization and developed some general comparisons. The goal was to provide the team and project sponsors with a more accurate picture of time expectations.

When Sandra took on the training management role, she realized her team lacked a set standard for project timeliness—but needed one. She embarked on her own study to learn how our research data applied to the work happening inside her organization and developed some general comparisons. The goal was to provide the team and project sponsors with a more accurate picture of time expectations.

Content

She also partnered with SITE to obtain a stratification of insurance organizations to complete her study. Our original research was based on one hour of training as the standard, and Sandra wanted to know if other insurance entities had a general development time standard. Based on responses from 17 organizations and 53 respondents, she discovered that 67 percent of respondents did not have a standard. Instead, “guess-timating,” self-created standards, and other deadlines were key factors in determining how long it takes to develop the training.

She also partnered with SITE to obtain a stratification of insurance organizations to complete her study. Our original research was based on one hour of training as the standard, and Sandra wanted to know if other insurance entities had a general development time standard. Based on responses from 17 organizations and 53 respondents, she discovered that 67 percent of respondents did not have a standard. Instead, “guess-timating,” self-created standards, and other deadlines were key factors in determining how long it takes to develop the training.

Content

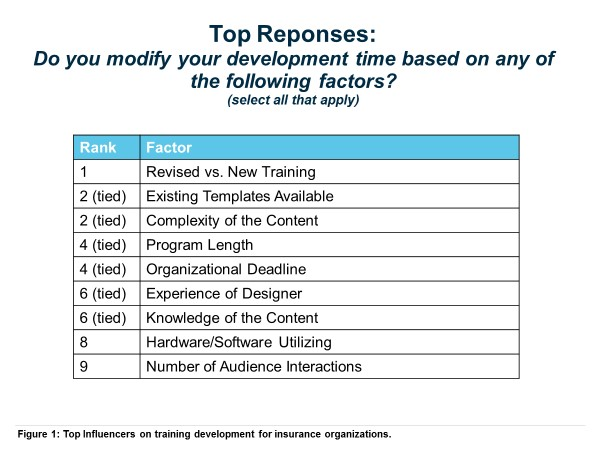

In addition, the notion of an “hour” of training had little relevance. Sandra asked respondents who did use a standard one hour of training (33 percent of respondents) to pinpoint which factors had an impact on the standard. The top influencers were whether the training is a new development versus a revision, if templates are being used, and the complexity of the content. (See Figure 1.) Sandra’s data tells us that a standard is helpful in its “as is” status, but also as a flexible baseline that can be adjusted based on the specific organization or project dynamics.

In addition, the notion of an “hour” of training had little relevance. Sandra asked respondents who did use a standard one hour of training (33 percent of respondents) to pinpoint which factors had an impact on the standard. The top influencers were whether the training is a new development versus a revision, if templates are being used, and the complexity of the content. (See Figure 1.) Sandra’s data tells us that a standard is helpful in its “as is” status, but also as a flexible baseline that can be adjusted based on the specific organization or project dynamics.

Strengthening Comparisons

Content

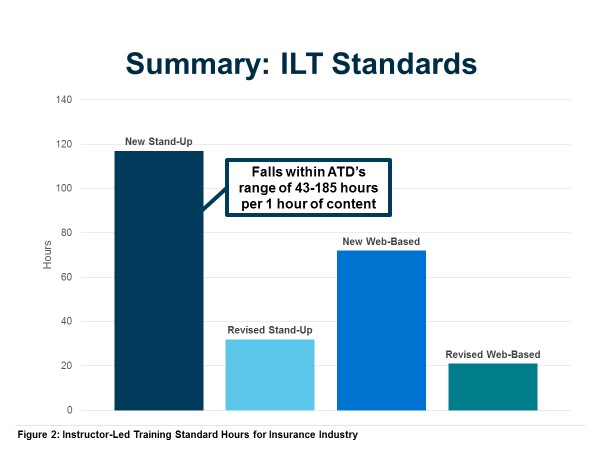

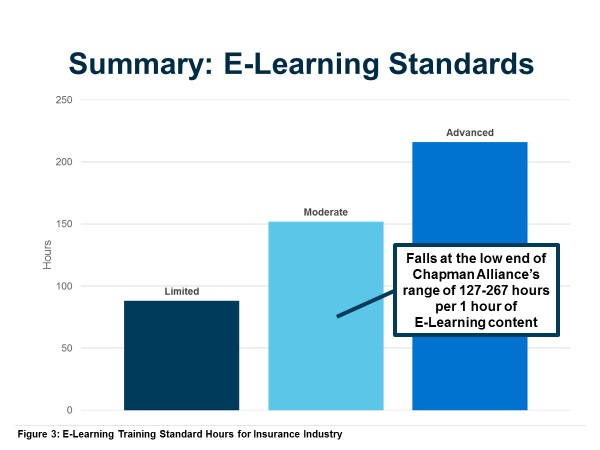

When it came time to analyze the data, Sandra compared her data to the 2009 research published by ATD and similar research released by the Chapman Alliance . Interestingly, Sandra’s ILT responses fell within ATD’s numbers (see Figure 2), whereas e-learning fell within the low end of Chapman’s ratios (see Figure 3). The difficulty in these comparisons is that each set of data was produced using a different study design. ATD’s study had more vendors respond than internal learning developers. In contrast, Chapman’s research includes vendors and L&D representation from 18 industries. Sandra’s respondents were internal to an organization and industry-specific.

When it came time to analyze the data, Sandra compared her data to the 2009 research published by ATD and similar research released by the Chapman Alliance. Interestingly, Sandra’s ILT responses fell within ATD’s numbers (see Figure 2), whereas e-learning fell within the low end of Chapman’s ratios (see Figure 3). The difficulty in these comparisons is that each set of data was produced using a different study design. ATD’s study had more vendors respond than internal learning developers. In contrast, Chapman’s research includes vendors and L&D representation from 18 industries. Sandra’s respondents were internal to an organization and industry-specific.

Content

After reviewing all the data, Sandra concluded that a time standard was valuable to an organization, but that it needed to be defined by industry- and organization-specific factors. To find that sweet spot for her learning organization, Sandra recommended:

After reviewing all the data, Sandra concluded that a time standard was valuable to an organization, but that it needed to be defined by industry- and organization-specific factors. To find that sweet spot for her learning organization, Sandra recommended:

Content

selecting an hour standard that is appropriate for her team’s processes, skill set, and culture

selecting an hour standard that is appropriate for her team’s processes, skill set, and culture

Content

tracking the team or organization’s development hours

tracking the team or organization’s development hours

Content

reviewing and revising the hour standard as needed.

reviewing and revising the hour standard as needed.

Content

For her specific organization, Sandra selected the ATD research as a starting point, but reduced those numbers by 50 percent for a learning revision and by 25 percent for a new learning initiative. That recommendation was made after considering her training teams’ familiarity with content, skill level of the team, use of templates, and a standard development process. Since accepting—and applying—these standards, Sandra’s team has been tracking their development hours to verify the baseline.

For her specific organization, Sandra selected the ATD research as a starting point, but reduced those numbers by 50 percent for a learning revision and by 25 percent for a new learning initiative. That recommendation was made after considering her training teams’ familiarity with content, skill level of the team, use of templates, and a standard development process. Since accepting—and applying—these standards, Sandra’s team has been tracking their development hours to verify the baseline.

Content

After a year of tracking, the initial findings show that across three completed learning initiatives the development team ended up taking 20 percent and 22.5 percent longer than their set standard on two of the projects. The increase was due to the incorporation of a new technology. More time was required because the team needed to determine where to incorporate the technology into the training content, and needed to collaborate with the vendor to pilot the technology. The third project’s development time was 30 percent faster than the training team's standard. The improved time was attributed to a tenured designer working on familiar ILT content.

After a year of tracking, the initial findings show that across three completed learning initiatives the development team ended up taking 20 percent and 22.5 percent longer than their set standard on two of the projects. The increase was due to the incorporation of a new technology. More time was required because the team needed to determine where to incorporate the technology into the training content, and needed to collaborate with the vendor to pilot the technology. The third project’s development time was 30 percent faster than the training team's standard. The improved time was attributed to a tenured designer working on familiar ILT content.

Content

Instead of completely revising the standards altogether, Sandra encourages her team to flex hours from the standard as needed to determine development timeline. More unknowns (for example, a new technology) will warrant an increase in hours from the standard. Conversely, the more knowns, such as the skills of the designer or use of a template, will decrease the hours.

Instead of completely revising the standards altogether, Sandra encourages her team to flex hours from the standard as needed to determine development timeline. More unknowns (for example, a new technology) will warrant an increase in hours from the standard. Conversely, the more knowns, such as the skills of the designer or use of a template, will decrease the hours.

Content

Sandra’s final recommendations align with our 2018 suggestions for creating a standard that reflects a profile of the learning organization. Meanwhile, she also denotes team processes, skill sets, and culture as factors for the insurance industry.

Sandra’s final recommendations align with our 2018 suggestions for creating a standard that reflects a profile of the learning organization. Meanwhile, she also denotes team processes, skill sets, and culture as factors for the insurance industry.

Showcase Highlights

Content

Sandra’s work exemplifies a great starting point for her industry and organization. If you are feeling the urge to answer the “why” for your organization or industry, here are some prompts to assist you in getting started.

Sandra’s work exemplifies a great starting point for her industry and organization. If you are feeling the urge to answer the “why” for your organization or industry, here are some prompts to assist you in getting started.

Content

To develop industry guidelines, you want to think about finding a common ground from which all entities can work and use the data you collect. Consider the following:

To develop industry guidelines, you want to think about finding a common ground from which all entities can work and use the data you collect. Consider the following:

Content

What is a common length of time for training programs in your industry?

What is a common length of time for training programs in your industry?

Content

What delivery formats are common in your industry?

What delivery formats are common in your industry?

Content

What level(s) of interaction are most commonly used in your industry?

What level(s) of interaction are most commonly used in your industry?

Content

What are common constraints (such as regulatory, shifting priorities, and so forth) in your industry that may play a part in developing a standard?

What are common constraints (such as regulatory, shifting priorities, and so forth) in your industry that may play a part in developing a standard?

Content

Does your industry rely on internal training departments, vendors, or a mix?

Does your industry rely on internal training departments, vendors, or a mix?

Content

What methods are commonly used in your industry for estimating time for development?

What methods are commonly used in your industry for estimating time for development?

Content

To develop organization guidelines, you can modify the industry questions. Here are a few additional prompts:

To develop organization guidelines, you can modify the industry questions. Here are a few additional prompts:

Content

What data is your organization currently collecting on its processes for developing learning?

What data is your organization currently collecting on its processes for developing learning?

Content

Does your team know the average amount of time, money, and talent you need to generate a common learning initiative for your organization?

Does your team know the average amount of time, money, and talent you need to generate a common learning initiative for your organization?

Content

Does your team/department have a development tracking system or process that provides a view of the above factors? If yes, can the information be used to project necessary time, money, and talent to ensure the project kicks off with a strong foothold?

Does your team/department have a development tracking system or process that provides a view of the above factors? If yes, can the information be used to project necessary time, money, and talent to ensure the project kicks off with a strong foothold?

Content

Do you have a profile of each team member on your L&D team? If yes, have you mapped the talents of the team to the most common demands placed on your department? If not, do you know the gaps, redundancies, and potential professional development needs of your team/team members?

Do you have a profile of each team member on your L&D team? If yes, have you mapped the talents of the team to the most common demands placed on your department? If not, do you know the gaps, redundancies, and potential professional development needs of your team/team members?

Content

As a final point, it’s important to define or operationalize your terms. For example, we made sure in our research that there was a clear definition of what the interaction levels meant. If you want good data, you will need to reduce the subjectivity within it.

As a final point, it’s important to define or operationalize your terms. For example, we made sure in our research that there was a clear definition of what the interaction levels meant. If you want good data, you will need to reduce the subjectivity within it.

What’s Your Case?

Content

Maybe you are doing similar research that is organization specific. What does your case look like? Let’s keep the conversation going. To share your work, contact me at [email protected] .

Maybe you are doing similar research that is organization specific. What does your case look like? Let’s keep the conversation going. To share your work, contact me at [email protected].